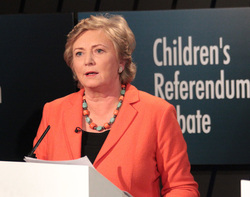

Minister for Children and Youth Affairs 2012: Frances Fitzgerald

The Childrens Referendum: Useful Infomation links

The Children Referendum, click here.

The Referendum Commission, click here.

Barnardos, click here.

Referendum.ie, click here.

The Children Referendum, click here.

The Referendum Commission, click here.

Barnardos, click here.

Referendum.ie, click here.

| Thirty First Amendment of the Constitution (Children) Bill.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1452 kb |

| File Type: | |

Children's Referendum: Summary of Wording

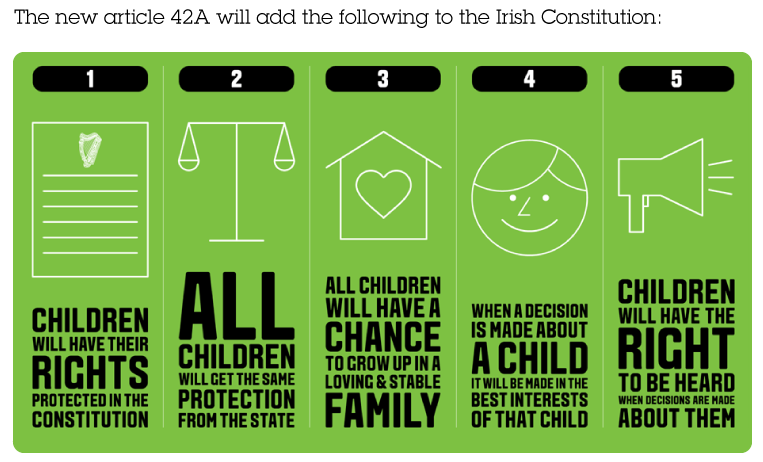

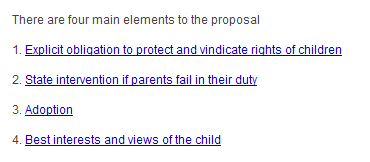

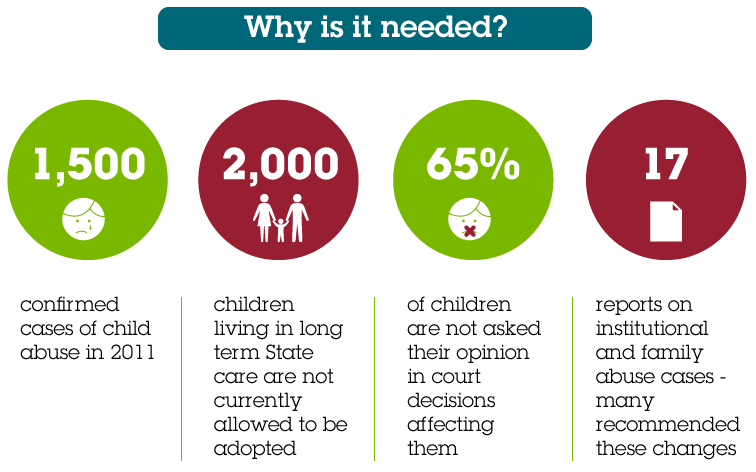

The Children’s Referendum will insert a new Article into the Constitution. The new Article, ‘Children’, will be numbered Article 42A and will sit between Articles 42 and 43.

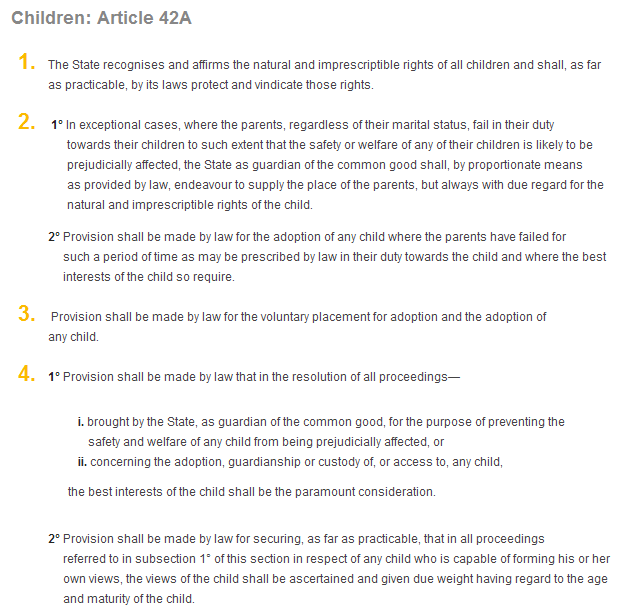

Article 42A.1 recognises that all children have rights and pledges to protect those rights by law. It allows the courts to identify rights for children on a case-by-case basis. This provision will enable the courts to develop new thinking in relation to children’s rights and to break with past decisions, some of which have resulted in bad outcomes for children.

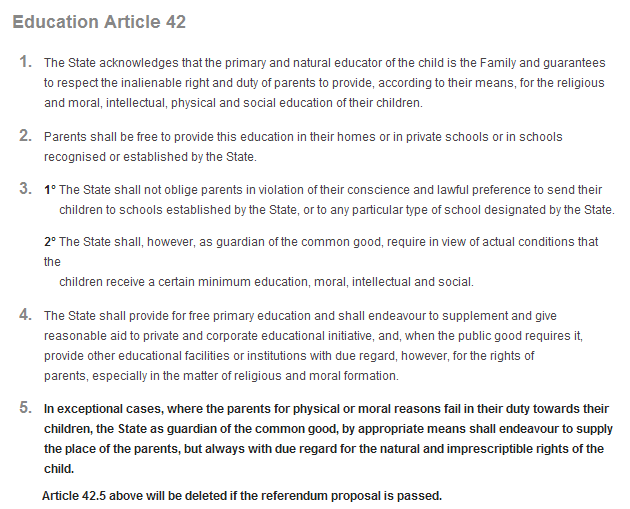

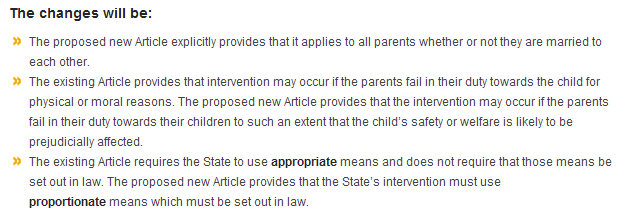

Article 42A.2 contains two parts. Article 42A.2.1 clarifies how and when the State can step in to protect children. It is an amended version of an existing Article in the Constitution (Article 42.5), which it will replace. Importantly, it shifts the trigger of intervention from focusing solely on the parents’ failure to the impact of that failure on the child. It provides a strong constitutional foundation for our child protection system, by providing the State with the power to act when the “safety or welfare” of a child “is likely to be prejudicially affected”.

This new wording should encourage the State to intervene earlier in families that are struggling to offer them support and better protect the child. Importantly, it also contains safeguards to protect against over-intervention by the State, by including the phrases ‘exceptional cases’ and ‘proportionate’. It provides, for the first time, the same threshold of protection to children, regardless of whether their parents are married or unmarried.

Under the Constitution at present, the best interests of children from married parents are presumed to be found within the child’s family without investigating whether this is the case in reality. This provision could be used to challenge this presumption in cases where the child’s “safety or welfare” is at risk.

Article 42A.2.2 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law to allow a child the opportunity of being adopted, where the parents have met a high threshold of failure towards their child. This law must set out the length of time that parents have failed in order for the child to be eligible for adoption. Critically, such adoptions can only take place where it is in the best interests of the child and where all other options have been explored and failed.

Alongside the amendment wording, the Government published draft legislation on adoption

[http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/bills28/bills/2012/7812/b7812d.pdf] which sets out what will change in the area of adoption, if the referendum is passed. Under this draft legislation, there must have been a continuous failure on the part of the parents towards the child for a period of 36 months (three years). There must also be no reasonable prospect of the parents resuming care of the child, and the child must have been living in the home of their prospective adoptive parents for a minimum continuous period of 18 months.

Article 42A.3 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law that allows parents, either married or unmarried, to voluntarily place their child for adoption and consent to the adoption of their child. At present, this is not legally possible.

Article 42A.4 contains two parts. This Article is unique to the Constitution in that it legally obliges the Oireachtas to define these rights and to make sure that relevant legislation is in place.

Article 42A.4.1 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law that ensures the best interests of the child will be “the paramount consideration”, in certain areas of decision making affecting a child. This means those decisions will be determined based on what is best for the child in question. It applies only to proceedings:

brought by the State involving children in the care system and child protection cases; and

concerning the adoption, guardianship or custody of, or access to, any child.

Article 42A.4.2 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law to ensure the views of the child are taken into account in the proceedings listed in 4.1 (children in care, child protection, adoption, guardianship, custody and access cases). This does not mean that the child’s views will be the determining factor in the case. Rather, the child’s views will be considered by the judge and given due weight according to the child’s age and maturity. At present, the views of the child are heard on an ‘ad hoc’ basis, and whether the child is given the opportunity to be heard or not largely depends on the type of case before the Court and the judge hearing the case. Such gaps will be addressed by this new wording.

The Children’s Referendum will insert a new Article into the Constitution. The new Article, ‘Children’, will be numbered Article 42A and will sit between Articles 42 and 43.

Article 42A.1 recognises that all children have rights and pledges to protect those rights by law. It allows the courts to identify rights for children on a case-by-case basis. This provision will enable the courts to develop new thinking in relation to children’s rights and to break with past decisions, some of which have resulted in bad outcomes for children.

Article 42A.2 contains two parts. Article 42A.2.1 clarifies how and when the State can step in to protect children. It is an amended version of an existing Article in the Constitution (Article 42.5), which it will replace. Importantly, it shifts the trigger of intervention from focusing solely on the parents’ failure to the impact of that failure on the child. It provides a strong constitutional foundation for our child protection system, by providing the State with the power to act when the “safety or welfare” of a child “is likely to be prejudicially affected”.

This new wording should encourage the State to intervene earlier in families that are struggling to offer them support and better protect the child. Importantly, it also contains safeguards to protect against over-intervention by the State, by including the phrases ‘exceptional cases’ and ‘proportionate’. It provides, for the first time, the same threshold of protection to children, regardless of whether their parents are married or unmarried.

Under the Constitution at present, the best interests of children from married parents are presumed to be found within the child’s family without investigating whether this is the case in reality. This provision could be used to challenge this presumption in cases where the child’s “safety or welfare” is at risk.

Article 42A.2.2 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law to allow a child the opportunity of being adopted, where the parents have met a high threshold of failure towards their child. This law must set out the length of time that parents have failed in order for the child to be eligible for adoption. Critically, such adoptions can only take place where it is in the best interests of the child and where all other options have been explored and failed.

Alongside the amendment wording, the Government published draft legislation on adoption

[http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/bills28/bills/2012/7812/b7812d.pdf] which sets out what will change in the area of adoption, if the referendum is passed. Under this draft legislation, there must have been a continuous failure on the part of the parents towards the child for a period of 36 months (three years). There must also be no reasonable prospect of the parents resuming care of the child, and the child must have been living in the home of their prospective adoptive parents for a minimum continuous period of 18 months.

Article 42A.3 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law that allows parents, either married or unmarried, to voluntarily place their child for adoption and consent to the adoption of their child. At present, this is not legally possible.

Article 42A.4 contains two parts. This Article is unique to the Constitution in that it legally obliges the Oireachtas to define these rights and to make sure that relevant legislation is in place.

Article 42A.4.1 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law that ensures the best interests of the child will be “the paramount consideration”, in certain areas of decision making affecting a child. This means those decisions will be determined based on what is best for the child in question. It applies only to proceedings:

brought by the State involving children in the care system and child protection cases; and

concerning the adoption, guardianship or custody of, or access to, any child.

Article 42A.4.2 commits the Oireachtas to bring in a law to ensure the views of the child are taken into account in the proceedings listed in 4.1 (children in care, child protection, adoption, guardianship, custody and access cases). This does not mean that the child’s views will be the determining factor in the case. Rather, the child’s views will be considered by the judge and given due weight according to the child’s age and maturity. At present, the views of the child are heard on an ‘ad hoc’ basis, and whether the child is given the opportunity to be heard or not largely depends on the type of case before the Court and the judge hearing the case. Such gaps will be addressed by this new wording.